- Home

- Justin Olson

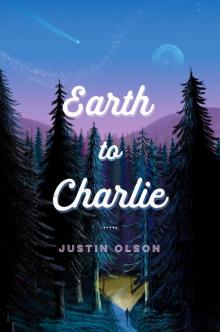

Earth to Charlie

Earth to Charlie Read online

To those who look up

When it’s all over, desire doesn’t die.

—Karen Fiser

PART ONE

ZEROING IN ON THE INFINITE

THE GREAT WHITE SHOCK

• • • • •

My mind drifts from one thought to the next. My bedsheets are finally warm. I roll to one side, then to the other. After a bit of adjusting, I find myself on my back. My eyes shut.

I wait restlessly for sleep to find me.

The house is so deadened of people and activity that the air feels heavy and stagnant. If someone were to walk into my room right now, they’d think it was a tomb.

And I, the body.

Lying here, I think of this time when I was five, and my mom was watching me in front of our house. I was riding my tricycle on the sidewalk, and I flew past her and shouted, “I’m flying!” I always believed I was a plane pilot on my tricycle, and later on my bike. But I’ve outgrown make-believe.

I rode back, and she smiled, her perfect white teeth showing in the bright sun, the bandana holding her wild hair in place, and she pointed up. She said, “You were in the sky, Charlie. You’re the best pilot in the world.”

I laughed and repeated, “I’m the best pilot in the world!” I pedaled down the road, before turning my tricycle around to face her.

I stared at the road—the imaginary runway—as it continued on in front of me for what seemed like forever.

My flashback is cut short when I hear a large buzz coming from outside my window. It sounds electric—like a weed-eater. Only, it’s so loud that I have to cover my ears. But the buzz is secondary to the light, which flashes so brightly I’m momentarily blinded.

I sit up with a start and see the white light dissipate as rapidly as it arrived. I grab my glasses on the nightstand, and within a half second I am at my window, pulling up the blinds and staring out across the night sky. I see nothing, but that doesn’t stop me from darting out of my room, down the wooden stairs, and out the back patio door. My bare feet feel cold as I run through the blades of grass. The night air cools my arms and legs too. But I have to run after that light. I have to follow it, and when I make it to the edge of my yard, I realize I am trapped by our chain-link fence. Standing there, under the crystal clear sky, I worry that the light is long gone.

Then again, it might have landed somewhere near me, in the forest.

As this is the first time—and might be the only time—I’ve witnessed a likely UFO encounter, I have no choice but to chase it.

I bolt inside and run up the stairs for my shoes and hoodie.

I flip on my bedroom light and see the mess that is my bedroom. The floor is a swirl of clothes, magazines, books, more clothes. I look for my socks but can’t find any. “Come on!”

There’s one white sock under a sweater. I toss books aside and find a black sock. It’ll have to work. Time isn’t on my side, and I’m getting frustrated.

I grab a sweater, which says WHITEHALL HIGH TROJANS on the front in purple letters, with a purple armored helmet underneath. I hate this sweater, but it’s the only one within reach. As I turn to my door, there’s a silhouette blocking my escape.

“What in the Lord’s name are you doing? You should be in bed.” Even five feet away, I smell the beer on his breath and clothes.

“I have to . . .” I can’t tell him.

Not moving from the door, my dad seems like he gives zero shits about my frantic pace.

“I need to go!” I say. “I’ll be back soon.” Though, I hope that’s not true.

“It’s a school night, Charlie. You’re not going anywhere.”

My dad, even drunk, can enforce his parental responsibilities. He works at the Golden Sunlight Mine and always has a five-o’clock shadow and dirt under his fingernails. His clothes always look like they should’ve been shredded into rags years ago.

I bounce on the balls of my feet. “Come on, Dad. Please!”

This is a matter of life and death, after all.

Moseying into my room as if he has all the time in the world, he says, “This better not be about some UFO nonsense.”

I notice that as my dad approaches me, my door is left wide open, so I dart past him. But I trip on a pile of clothes, and the next thing I know, I’m facedown on the floor. I roll over, and my dad is towering above me like a giant.

My heart beats heavily at the thought of the UFO flying away.

Leaving me here.

I just stare at my dad. He makes no effort to help me up. Instead he walks to my window and searches the sky. “Nope. Nothing out there. Nothing ever out there.” The blinds hit the windowsill with a definite thud. He lets go of the string and steps over me and heads to the door.

“Get to bed. But I’m glad to see you’re wearing your birthday present.” He starts to close my door but then stops. “And you know better than to try to run away like that. What has gotten into you?” My bedroom door slams shut, and my world shakes. I sit on the floor, unable to chase after the one thing that came to save me. Though, my search is far from over.

MY HISTORY

• • • • •

I am wide awake because I’ve let the one and only thing I’ve spent years trying to find escape. Why did I let it get away so easily? Why didn’t I just leave my room after my dad went to bed? I have squandered the greatest opportunity of my short, pathetic life—the opportunity to finally be reunited with my mother.

I toss and turn in bed and try to calm my mind. I think about the moments that led me to this night.

I started scanning the sky in seventh grade, the night after she disappeared, and I used binoculars in my bedroom. On the first night of searching, I saw something moving and blinking. I got so excited that I jumped up and down. My search for aliens had been almost too easy. But when I put the binoculars back up to the sky, I could no longer find the blinking light.

The following night, at about the same time, I saw the same blinking light in roughly the same place. That was when I knew something was wrong. What I had been focusing on was too steady, too noticeable. It dawned on me: a satellite. My shoulders slumped in defeat.

As I kept searching, I realized that binoculars were not helpful. It’s too hard to see anything with them in the dark, and they started giving me a headache. Besides, if a UFO were near, would I even need binoculars?

I began to leave the house to search the night sky. While I loved the unobstructed view, I missed my second-story vantage point. So I started hiking into the woods and up onto a hill not too far from my house. But my dad got suspicious that I was searching for UFOs, and he told me I couldn’t go into the woods at night anymore (but he was rarely around to enforce his rule so I just made sure I was home before him).

I’ve also spent hours upon hours looking up UFOs online, so I know what to watch out for. Of course there’s the usual spacecraft: discs, saucers, pretty much what we see in alien films. They are usually gray or black. But there are also some weird UFO shapes that you’d never really consider: pyramids/triangles, bowls, spheres, and oblong shapes. That’s just scratching the surface. Until tonight I hadn’t personally seen a UFO. At least what I would assume is a UFO. Maybe there’s one right outside my house, and I can’t see it. Or it has disguised itself as something else . . . like a satellite. . . . But I really don’t think about that kind of stuff, or I’d get depressed and paranoid, knowing they’re so close and still so out-of-reach.

It’s now the dead of night, and I yawn, stretching my body, but I can’t will myself to close my eyes. I wonder if Meridian X saw this.

The summer of my eighth-grade year, I drew a map of the stars. It wasn’t a great map, but it took weeks to draw, as I had to keep looking up. I broke up the sky into segments

so that I could search each grid more in depth for UFOs and mark each section off as I went. Only problem? The earth rotates and the sky changes—the stars are constantly dancing and jumping, and planets are coming in and out of view. So by the time I was done with one section of the sky, the entire sky had shifted, and I quickly saw the futility of my endeavor.

Maybe all this sounds so simple and obvious, but I didn’t know anything when I started. It was my own learning experience.

Now I get up and go to my bedroom window. I look up—knowing so little about the vastness above me and feeling small and insignificant.

How could I have just let the UFO get away?

IT WAS THE BEST OF TIMES . . . BUT MOSTLY IT WAS THE WORST OF TIMES

• • • • •

As I head down the oppressive school hallway to Ms. Monakey’s room for first period on the last week of school, I hear, “Write anything today, Charles DICK-ens?” Joey turns to his two idiot friends, Matt and Psych, and laughs. They always sound like a bunch of donkeys when they laugh, which is why I’ve dubbed them the Ass Trio. Oh, and they’re assholes. That’s why too.

This is just one of the many jabs I hear throughout the course of a given school day. It actually amazes me that these Neanderthals still get pleasure out of such stale material. I ignore them and continue on.

I believe that my parents set me up for constant bullying, though I have come to believe it wasn’t on purpose—which has kept me from hating them.

See, my name is Charlie Dickens. It’s not “Charles”—like the famous author. Even my birth certificate says “Charlie.”

The first day I came home in a rather sour mood was in third grade, because I had been teased about my name. My mom told me that even as a little girl she had dreamed of having a boy named Charlie. Even back when her maiden name was Severson. I had no problem with my first name.

The problem came because my dad’s last name is Dickens.

I don’t think either one of my parents had read a Charles Dickens novel in their lives. Though, they had to have at least heard the name. Had to have known about him. So how either one didn’t put two and two together, I do not know. And their lack of forethought has haunted me to this day.

Okay . . . so the story isn’t so cut-and-dried (like most decent stories). My mom had been told up until the day I was born that she was having a girl. So when out popped a boy, her eyes lit up and she said, after having been in labor for ten and a half hours, “It’s my own baby Charlie.”

Little Charlie Dickens. That name—those two words—have trapped me, and will forever.

* * *

I’m sitting in Ms. Monakey’s classroom waiting for the bell to ring. There’s this website called Montana UFO Sightings. (Original, right?) It’s maintained by a woman who calls herself Meridian X, who lives in Butte—a town about thirty miles west of here. I’m checking to see if there are any reports of UFOs from last night in the Whitehall area. I need to find some validation.

As last night grew longer, I began to convince myself that I was crazy for thinking I’d seen a UFO. How could my dad not have heard the noise or seen the explosion of white light?

Did I make it up?

Did I actually fall asleep and dream it?

I see no new activity on the website, which doesn’t mean last night’s event didn’t happen. It could just mean that Meridian X is slow at updating a website that looks like it was made in the early 2000s.

Next thing I know, someone’s hot breath is tickling the hairs on my neck. I assume it’s some jerk trying to be funny, and I turn to see the new kid leaning over the desk behind me. “There’s really a website for Montana UFO sightings?”

I quickly exit out of the internet browser and feel my face grow warm. I shouldn’t be so careless. “Mind your own business.”

Okay, so not the most welcoming sentence, but after years of constant teasing, I’m always on guard.

“Sorry. Just trying to make conversation.” The new kid’s name is Seth, and he leans back in his chair and pulls out his phone.

I adjust my glasses and then decide to ask, since there really are only a couple of people in the classroom, and none are paying attention to us. “Were you awake around midnight last night?”

“Shouldn’t I mind my own business?”

“Sorry. I thought you were going to make fun of me or something. That’s why I said that. I’m just wondering if you happened to hear a loud buzz or a see a white light?”

Seth’s eyebrows draw in, and his lips purse together. “Hmmm. You know, I think I did. But I think it was just a semi or something, and I had headphones on.”

“Really?” This was great validation.

Well, sort of validation.

“Do you believe it was a UFO? Is that why you were on that site?” he asks.

Not wanting him to tease me, I shrug. “Doubt it.” Though, it’s only a matter of time before he gets the memo and starts teasing me anyway. Or realizes on his own that I am the school’s outcast. But to be honest, it feels oddly safer to be alone and wrapped in a cocoon of my own making.

First period Spanish is the only class I have with the new kid, which means he’s not a freshman like me. But the school is small enough that I see everyone all the time. Unfortunately. I even see those I never want to see another day of my life (like the Ass Trio). I’ve noticed that the new kid has worn a camera around his neck every day. It looks like one of those expensive professional-photographer cameras. It’s actually pretty sweet.

The bell rings, and Ms. Monakey stands in front of the room and clasps her hands together. “All right, class. ¿Están listos? Let’s begin.”

But between a possible UFO sighting and talking to the new kid, my mind is too distracted to pay attention. I’m wondering why Seth moved to Whitehall so close to the end of the school year, but it’s really none of my business, is it? This is all I know about him, from his first day in class, nearly two weeks ago:

Ms. Monakey asked him to come to the front of the room. She said, “Este es Seth. Seth es nuevo aquí.” She looked at him. “Do you want to tell us a little about yourself?”

Seth looked around the room and lingered a second on my eyes before saying, “Oui. My name is Seth. Seth is new here.” He chuckled. “Just kidding. I’m from—”

Ms. Monakey corrected him, “Soy de.”

“Oh, right. Soy de Miles City.”

“¡Maravilloso!”

“No. Terrible. Muy mal. I was hoping Whitehall would have fewer rednecks than Miles City, which should be easy for any city to achieve. But so far I’ve been woefully disappointed.” He went to sit down, but stopped. “Oh, and . . . Yo amo fotografía.” He held up his camera. “And trashy televisión.”

As he passed by my desk, I felt like he looked at me again and held my gaze a little longer. It was uncomfortable, but maybe I’m just not used to positive attention at school.

FORGETFUL ELOISE IS STILL ALIVE

• • • • •

My grandmother lives in a room about the size of two regular-size closets. Not only is it small, but it’s as bland as white bread and as inviting as a frigid snow-covered field in the middle of Montana. Her cheap blinds are rarely open, which means the room is always too dark. There is a bed with metal handrails that are able to rise from each side. Next to the single bed is a small nightstand with a clock that I always set to digital time, but it refuses to stay in sync.

The state pays for the room because my grandmother ran out of money back during Obama’s first term. Although, if you were to ask her—and her name is Eloise Dickens—what money is, she’d probably just blink at you. And maybe smile, but that would depend on your tone.

Every time I walk in, I shake my head and pull open the blinds. “Don’t you want to see something, Grandma?”

I love describing the sky to her. It’s like a painting to me, and like any artwork, the possibilities of describing it are endless. And although I could never paint anything as amazing

, I like to try describing what I see as if I’m the artist.

“Hmmm.” I ponder thoughtfully. “I’m seeing turbulent clouds on a rocky sea of blues.” I pretty much just make things up, while trying to sound artistic and maybe somewhat pompous. Nobody but me is listening anyway.

My grandma almost always sits in her faded pink recliner. Normally she’s watching The Doctors when I arrive after school. The Doctors is this lame “medical” show, but really it’s just entertainment with all these attractive-looking people giving “medical” advice. Though, I also use the term “watching” loosely. My grandmother has no idea what is being said on that show. But her real doctor, at the nursing home—his name is Dr. Book—says that she likes the noise. I honestly don’t know how he knows that, because I doubt my grandmother has ever said, “I like the TV on for the noise.” Especially because my grandmother doesn’t really have cogent thoughts anymore. But I don’t question the doctor.

The clock is out of sync, even though I adjusted it yesterday. I go over and adjust it back two minutes. “No speeding up time,” I joke.

My grandmother just smiles. Her curly white hair rests tightly against her scalp.

I sit on her perfectly made bed, which she doesn’t make. “So, did you see that white light last night?”

“Light?” she asks.

“Yes. Around midnight. Did you see it?”

The nursing home that my grandmother stays in is only about five blocks from my house. My house, for reference, sits on the eastern edge of town. And Whitehall is a town. A town of maybe three thousand people. I figure the light would have been just as bright here.

“Yes,” my grandma says, “I’d like some.”

“No.” I shake my head. “Last night, Grandma. Did you see a bright light come from your window?” I point at the window, not sure if that helps or not.

She smiles and nods. “Nice window.”

I let out a small sigh, but I don’t get mad. I knew I wasn’t going to get any useful information from her. But I had to try. My grandma has been known to surprise me with lucid moments, and sometimes even a lucid day. But those haven’t happened for at least a year now, and Dr. Book doesn’t think they will anymore. Isn’t it kind of sad to think that you’ll never think clearly again? But I guess it’s only sad if you can think about it.

Earth to Charlie

Earth to Charlie